The Dangers of Overconfidence in Management Personnel

By Ryan Hobart

6 years agoOver the course of building a contending team, changes always have to be made. It’s not enough to draft the best rookies, put them at the top of your lineup, and wait for your Stanley Cup to arrive. We’ve all seen with the Buffalo Sabres how a management team, or possibly a specific General Manager in Tim Murray, can be successful in breaking things down, but not in building them back up. Will this be the case for your favourite team, too?

Looking at teams like the Maple Leafs, Oilers, and Flames, it’s easy to see how the breaking things down part went smoothly. Other teams like the Red Wings and the Canucks are still working on breaking things down, the latter doing better than the former in acquiring, but the former further along with young established talent. All of these teams have amassed some young talent over the last few drafts and through some trades. But are they going to make the next steps count? How can we make sure that they do?

The job of tearing a roster down has been repeatedly noted as the easier half of rebuilding. Really, how much credit does a GM deserve for picking up a superstar in the draft? Or multiple superstars? How hard is it to look at your roster, and trade every piece that lacks future value, for pieces that bring back future value?

In the construction stage, management personnel are faced with a real job. It seems like a completely different task from the one they’ve already succeeded in. It’s hard to know if the success they’ve had to date is even relevant in deciding if they’ll be successful going forward.

Responsibility and Reward

Let’s talk first about what it means to be part of the chain of command. Responsibility and reward are the two fundamental concepts involved in a management hierarchy. One flows upwards, and one flows downwards. Within this piece, I will be using the term “management” to mean any personnel in a managerial role, which to me would include the coaches, assistant GMs, people in Hockey Ops, GMs, and Presidents.

Responsibility flows upwards. The player is responsible for themselves, but the coaches are responsible for both themselves and the players. So on and so forth up the chain of command. On the other hand, reward (which in this and most other cases is money) flows downward. The money to pay the players is given out by the manager. The money the manager has to give out comes from the investors. But where does the investors’ money come from?

Hopefully, you figured it out where this is going. The revenue teams have to work with comes in part from its fans. You and I control a chunk of the revenue by choosing to participate. By watching the ads, by paying for the tickets, by buying the jerseys, etc. We share in the financing of our favourite hockey team. We’re a source of the reward.

Because of this, following our earlier description of the chain of command, we are also a part of the responsibility. We are somewhat accountable for the people on all of the lower links of the chain. This is a real thing that happens in real industries, and hockey is no different. Public perception is a huge factor for public companies. And while a hockey franchise isn’t a tax-funded organization, it certainly benefits from the financial investments that fans make.

Actions and Trust

With a portion of the responsibility in our hands, it’s important that we do something with it. That’s why seeing the blind faith that fans are putting in management is so frustrating. If we’re using our responsibility and power to be completely flippant, and trusting the people below us in the hierarchy to do their job properly without verifying that they are actually doing so, we’re creating a huge risk for ourselves.

When management makes a move and the masses jump to analyze it – we’re not saying that we believe we’re smarter than management. We’re saying that we care whether that decision was good or bad. By doing so, we’re putting pressure on our management to make moves that appease us, so that the money keeps flowing out of our bank accounts. We don’t have all-powerful control, of course, but we have some tangible influence.

This is all to say that what you say and how you analyze your team matters. Your voice matters, even among the sea of similar voices, even if you don’t say much, even if you have a minute Twitter following, and even if you come from a minority background. So when Kris Russell signs his extension with the Oilers, and fans are happy with it because they know that Peter Chiarelli is a competent GM, they are creating a situation where Chiarelli can sign whoever he wants without accountability to you.

Analysis and Critical Thinking

To look at the important of fans using their influence for good – look at the frustration that Leafs fans showed with Jonathan Bernier that saw the team move on from him. Bernier went on to post nearly identical (and in fact a little bit better) 5v5 Fenwick Save percentage (the best goalie number readily available with Corsica’s Adj. FSv% down for the time being) than new Leafs’ starter Frederik Andersen.

This is where the much-bemoaned “analytics” has to join the conversation. My critical thinking process almost entirely consists of consulting the best available predictive model to evaluate whether a decision was good or bad, and just how good or bad it might be. There’s always financial considerations, and intangible considerations as well, but the essentials of my opinion are based on those numbers.

Currently, that model is DTMAboutHeart’s Goals Above Replacement model. You can read about it over the course of several pieces here. You can find the data here for 2007-16 and 2016-17.

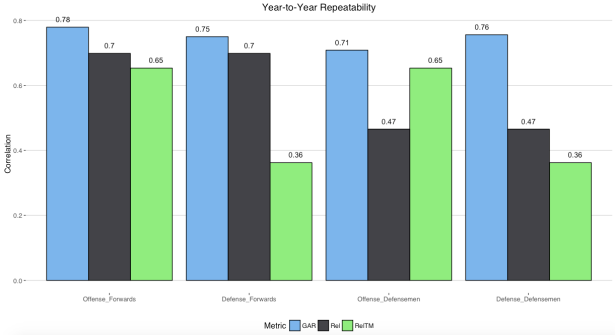

The key factors are repeatability (how sure are we that this player will continue to put up similar numbers) and predictive power (how sure are we that being good at this number means your team will win). The graphs below show how GAR stacks up against Corsi Rel and Corsi Rel TM, two models who together are probably still the most popular models existing. We can see that GAR blows it out of the water, and that’s why it’s an important factor in my evaluations, even as a fan.

To steal directly from the Testing and Final Remarks post on GAR:

Here is how the even-strength per 60 stats stack up against the most popular metrics currently used to evaluate a player’s value:

The point of hockey games is to win and teams win by scoring more goals than their opponents. This is why shot attempt metrics have gained such prominence in recent years, their value comes from their ability to predict future goals and future winning. I have based this test off a similar test done by Neil Paine. Since there are not many individual metrics currently available for special teams we will focus on even-strength metrics for these tests.The test will be conducted as follows: we will assume that for a given season we know exactly how much playing time each player will receive and use the player ratings from a previous season to predict their value in the next season.Player’s Rating in Year 1 * Player’s Playing Time in Year 2 = Player’s Predicted Value in Year 2.We will then sum each player’s Year 2 rating by team and we will see how well that team rating correlates with that team’s goals for and against total in Year 2. The lockout shortened season was removed from this study, as well as players whose Year 1 rating occurred while playing less than 300 even-strength minutes. Here are the results of that test:

To me, this indicates that GAR has much stronger repeatability and predictive power than what we’ve been using thus far, but it is still far from perfect. We obviously can’t treat it as gospel, but it is miles better than using no analytical information and instead evaluating based on subjective factors and eye tests which involve countless cognitive biases we can barely begin to account for.

Even if GAR is not your choice for analysis if your basis for opinion-making isn’t quantifiable, repeatable, and predictive in some fashion, what confidence do you have that you’re influencing your team in the right direction? The danger is: the team is going to hear you either way. They’re going respond based on your input, whether it’s factually supported or not. This is why I’ve been such a strong supporter of analytics in hockey fans’ conversations, and why I strongly recommend you do the same.

Conclusions

This piece is not intended to tell you that you have to include analytics in discussions, or that you have to make every effort to analyze management decisions going forward. It is simply a presentation on why I think that you should. All in all, it is important to me that fan bases do what’s best for their teams, and I hope this was a good list of reasons how and why you can and should do that.

All together, I only hope this sparks a new appreciation for the power that a fan can have, and creates a new consideration for basing opinions on predictive data whenever possible. It’s important to me that fans do their best to promote good decision-making and understand our role within that.

Recent articles from Ryan Hobart